The discussion “Is there anyone here who still uses slide rules?” on Hacker News reminded me of the children’s maths/puzzle book Nut-Crackers (1971) I once had, with cut-out paper slide rule at the back - and set me re-visiting what other mathematical games it had contained.

(For those unfamiliar with slide rules - they helped multiply numbers before electronic calculators were commonplace. For example, to calculate 4 x 5 with this simple slide rule, you line the initial “1” on the first slide with the “4” on the second, then read along to the “5” on the first slide and discover that it points to “20” on the second. Professional slide rules had more range and precision…)

Although the book was aimed at a young audience, some of the games and puzzles do link to more sophisticated topics. We see how mazes can be transformed to equivalent graphs (in the graph-theory sense of a network of nodes/vertices joined by lines/edges, not a chart showing statistical data), stripping out the twists and turns and focusing on what really matters, the junctions and how they are connected - and are shown some algorithms to solve them.

Map of Hampton Court Maze, and the equivalent simplified version, both from Nut-Crackers by John Jaworski and Ian Stewart.

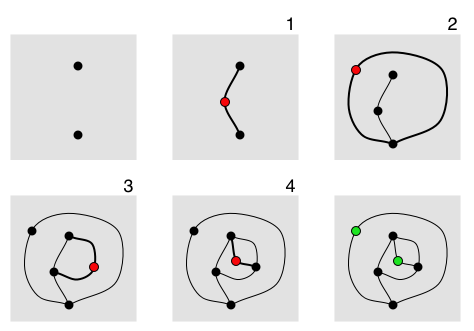

We are introduced to the game of Sprouts, also based on graph theory, which was invented in the early 1960s by John Conway (who also created the cellular automaton Game of Life) and which, despite the simplicity of its rules, has withstood intensive analysis of winning strategies in the decades since.

Image of the progress of a game of Sprouts starting with two dots by Maksim, from Wikimedia Commons, licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. Games with more dots in the initial state are trickier to analyse. It was found in 2025 that a game started with 100 dots can be won by the first player, a game started with 103 or 104 dots can be won by the second player, and that is as far as current reported analysis goes…

The “Splitting Field” puzzle, however, doesn’t atempt to show the young reader how to extend an algebraic field so that a polynomial can be split into linear factors, despite what students of Galois theory might have expected from the name. Instead, it is the rather simpler challenge of dividing an equilateral triangle of farmland into four plots the same shape. (Perhaps the title is the mathematician’s equivalent of a Parental Bonus?)

The challenge to find descriptions of numbers where the the number of letters in the description matches the number itself also looks interesting: FOUR is easy, TWELVE PLUS ONE and TWO CUBED are a step further on, while THE NUMBER OF THE BUS THAT PASSES OUTSIDE MY HOUSE is an option for the reader who live on the route of the 41.

And as I looked back at Nut-Crackers, I now notice was an early book (the first, Wikpedia suggests) from (along with John Jaworski) the subsequently prolific mathematician and writer, Ian Stewart!

In the HN discussion of slide rules, there was a comment from someone playing Balatro - a (very)-loosely-poker-inspired game where the points for your hand of cards are based on adding up chips and applying a multiplier - who had designed and 3D-printed a custom slide rule to help calculate scoring. That shows both dedication and how technology available to the hobbyist has progressed in the last 50 years…